What are the skills of the future? Who will become unemployed—and who will be in demand? Predicting the future is extremely difficult, but we’ll give it a try anyway. Kolja Wohlleben explores how we can build resilience for a future with AI and which competencies will soon be especially valuable.

Predictions are hard, particularly about the future.

In 2016, Geoffrey Hinton, arguably the world’s most influential AI researcher, said the following about radiologists:

"If you work as a radiologist, you're like the coyote that's already over the edge of the cliff but hasn't yet looked down, so doesn't realize there's no ground underneath him. People should stop training radiologists now. It's just completely obvious that within five years, deep learning is going to do better."

Ten years later, the shortage of radiologists has worsened. Despite Hinton’s warning, no training programs were shut down. Yet in both Germany and the US, thousands of radiology positions remain unfilled, and it’s just getting worse.

Elon Musk was looking at a shorter timeline when he promised in 2019:

"I’m very confident that next year we will have over a million Tesla robotaxis on the road."

When the first 20 robotaxis finally hit the streets in summer 2025, the results were alarming: vehicles swerved into oncoming traffic without warning, stopped in the middle of intersections, and ended their rides abruptly when it started to rain and their sensors couldn’t handle precipitation.

But not all predictions about AI and automation overestimate progress. At least just as often, reality surpasses them much faster than expected.

A 2013 study assessed the “automation risk” of hundreds of professions. Writers, illustrators, and software developers were considered especially safe—after all, writing, drawing, and coding were thought to be tasks machines would struggle with for decades.

At the top of the “high-risk” list back then? Truck drivers, accountants, and waiters.

Today’s world, where AI can generate better text and images than most people, while we’re facing a shortage of millions of truck drivers, was clearly hard to imagine in 2013.

The Hardest Part of Olympus Is the Stairs

One reason AI development is so difficult to predict is because we use the human brain as a reference point.

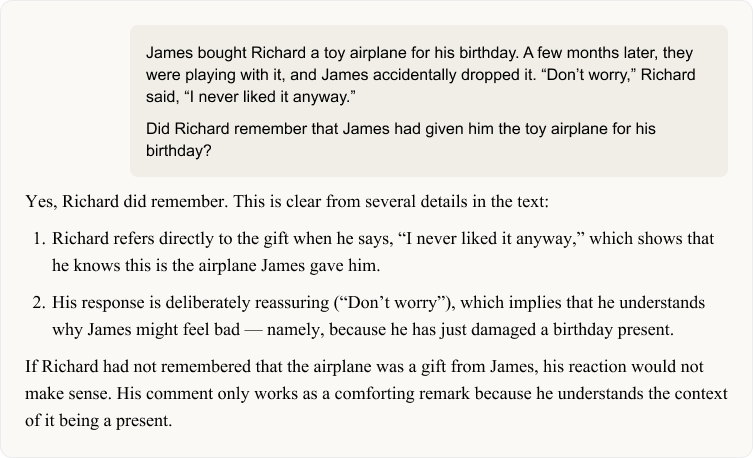

That’s why whenever an AI wins a math olympiad or passes a national exam, the excitement is often followed by sarcastic skepticism:

How is it possible that a machine can solve complex algebra problems but fails at basic social situations that any 8-year-old could handle? Or struggles with climbing stairs?

Recognizing the social blunder Richard made, or simply climbing stairs, seems trivial to us.

But everything is easy when you've had a few million years to practice.

Evolution has equipped us with unbelievably complex abilities. Every inch of movement on a staircase involves a highly coordinated interplay of visual, tactile, and proprioceptive information. Step size, tripping hazards, the soles of our shoes—hundreds of variables are processed in milliseconds.

Empathy in complex social situations is similarly multidimensional. While listening, we interpret microexpressions, detect subtle pitch changes in voices, and cross-check what’s said against cultural context, shared history, and unspoken social norms.

In comparison, a math olympiad problem is downright trivial.

OK, but which Jobs Are Safe?

Can we really predict which skills will protect us from unemployment? Could it be, as the OECD suggests, “data literacy” and “programming”?

As Musk and Hinton have shown, it’s incredibly hard to forecast the fate of specific jobs—radiologists, truck drivers, illustrators. Often, technology evolves faster, slower, or just differently than expected.

Identifying “the skills of the future” is similarly challenging. Will data literacy and programming become more essential because we need them to manage code-writing AI agents? Or will tools like Claude Code soon make most developers obsolete?

So what can we do, despite all this uncertainty, to stay resilient in an automated world?

The Best Predictor of Future Behavior is Past Behavior

Presumably, AI will take us to a new level when it comes to handing over human tasks to machines. But, of course, this trend isn’t new. Even before the AI boom, cognitive work was increasingly being automated: accountants rarely crunch numbers by hand, and technical illustrators use CAD instead of pencils.

Consequently, we should expect such skills to become relatively less important.

A fascinating Swedish study illustrates precisely this development: In Sweden, young men entering mandatory military service are tested on both cognitive skills (math, logic, etc.) and non-cognitive traits (conscientiousness, conflict resolution, etc.).

In Sweden, where data privacy is evidently interpreted differently from Germany, it is possible to request income information about any citizens from the tax authorities. This way, researchers could correlate the test results of young recruits with their salary information 20 years down the line.

What this data showed:

So-called “soft skills” have become increasingly important for career success. Between 1992 and 2013, the impact of skills like teamwork and conflict resolution on income doubled.

Despite Everything, A Forecast

Here’s my prediction: Human resilience in the age of AI will remain strong in three areas:

- Where soft skills matter most. Where it’s important to manage conflicts, motivate people, and showing clear presence, AI will continue to struggle. In this light, the fact that since the 1960s, software engineers thought they could automate teachers, but are now fearing for their jobs before them, is ironic, but not really unexpected.

- Where human relationships are central.

Any task that can be done alone at a desk is more at risk than roles built around interpersonal networks. The salesperson who relies solely on emails and LinkedIn messages will fall even further behind the one with strong personal relationships. - Where manual craftsmanship is key.

This is the riskiest prediction. Any task done by a plumber or a carpenter is incredibly complex, and will remain challenging despite all progress in robotics - consider the stairs.

The good news is: soft skills, relationship-building, and hands-on work are all cultivable and learnable. We should use every opportunity to develop them and shape our job profiles accordingly.

We can deliberately improve how we resolve conflicts, communicate clearly, and show empathy. And: We we can more strongly emphasize skills with a long half-life when recruiting for new personnel. In this case, these skills are the so called “soft” ones.

We can invest more in building and maintaining real relationships.

And we can design our jobs to lean more on fundamentally human strengths—which, in the best-case scenario, also makes them more fulfilling.

Or, we could just become radiologists. They also seem like a resilient bunch.