If despite ChatGPT and Copilot you're still not accomplishing several times more than before, it's probably not your fault: The promised AI-fueled productivity explosion has failed to materialize – what has spread explosively instead is the feeling of being productive. Kolja Wohlleben explains what's behind this, and how to approach AI constructively without rose-colored glasses.

One successful strategy to make money is convincing others that they’re not good enough.

The cosmetics industry, fashion sector, and nutrition consultants have successfully turned this insight into a business model: Only purchasing the right products and services ensures we become the best version of ourselves. Only with a collagen serum are we beautiful enough. Only with the new superfood turmeric are we healthy enough.

FOMO is a revenue guarantee. And so it's enormously valuable if organizational and personnel developers are wondering: "Are we productive enough?"

The New Gospel of Efficiency

Currently, the most profitable answer to this question is: "No, only if you use AI correctly will you be able to keep up" – preferably accompanied by the offer "And I'll explain how."

Archetypes for this pitch can be found on YouTube ("AI Productivity Hacks that will CHANGE your life – 90% don't know these features"), LinkedIn ("After 6 months of AI integration: Our productivity increased by 340% with our framework. Link to whitepaper in the comments"), but also where the discourse is actually defined:

The Grand Promises of the AI Evangelists

By OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, who speaks about programmers being "ten times more productive now." at the Federal Reserve. Or by NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang, advising young people against a career in software development because generative AI will do their job soon enough.

But all their strategic vision and intelligence don't immunize them against the power of their own financial incentives. The claim that software engineers are ten times more productive with AI than before is completely absurd. But Altman and Huang are parts of an industry built partly on inflated expectations. And it's famously unlikely that someone understands something when their salary depends on them not understanding it:

When Financial Incentives Distort the Narrative

This contributes to a discourse in which many ask themselves: Am I falling behind? Am I just missing the right whitepaper with the right framework to finally hack my productivity too? Could my employees automate half their tasks with good AI training?

From YouTube creators to CEOs, everyone seems to agree: AI multiplies your productivity – and if it doesn’t, it's probably your fault.

The only disagreement is whether this productivity gain will make us rich and happy (Altman) or unemployed (Huang).

But is that true? Is generative AI, as of October 2025, multiplying our productivity?

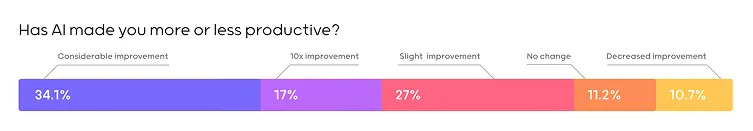

As for software development, many programmers actually do see it the same way Sam Altman does: 17% of all programmers who use AI at least sometimes (and that's almost everyone) estimate they've become ten times more productive through AI use, and another 51% report either a "significant" or "slight" improvement.

In other words: If the (self-)assessments of programmers and tech CEOs are broadly correct, we've experienced a multiplication of the average software developer's productivity in the last ~2 years. And what’s more: One in six has become productive enough that they can now take on the work of a ten-person team, alone.

Reality Check: Where’s the Boom?

Now: Do the years 2023-2025 feel like we've experienced an unprecedented productivity explosion?

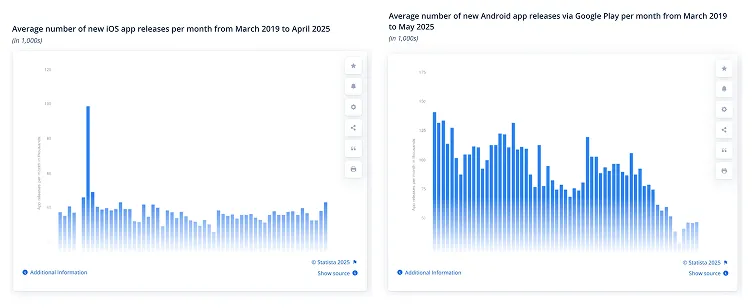

The blogger (and software engineer) Mike Judge did the work and collected data on new software releases in recent years.

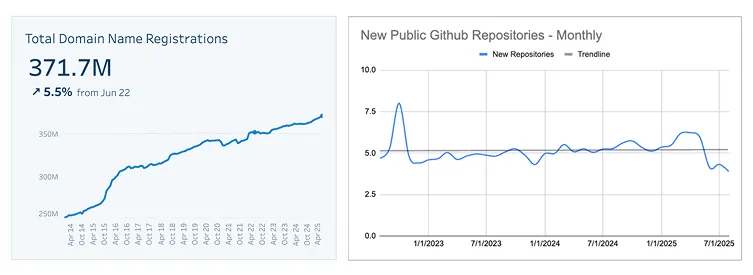

What we should see if the claims about productivity gains were true: More releases in Apple and Google's app stores, more website domain registrations, more games on Steam, and more code on Github. We should see enormous amounts of new software.

Quantity, Quality – or Nothing at All?

And yes, of course: Productivity increases can also flow into quality rather than quantity. But is it really conceivable that millions of software developers are suddenly able to develop more software – but none of them ends up developing more software?

What we actually see: Nothing. It's not that software gets finished a bit faster, just less so than the hype would suggest. No: In the last two years, nothing has changed regarding the number of monthly releases on any of these platforms since AI in coding became a thing.

No additional revenue from ad-financed mobile games, no independent web designers delivering a multiple of client projects? No hobby developers finally advancing their neglected personal projects? No security vulnerabilities that can now be closed twice as fast?

The claims of Sam Altman and AI "productivity experts" can be explained relatively easily with their business interests.

But could it be that the users themselves – in this case software developers – are really that far off? Is it possible that people who use AI every day for very concrete problems have such distorted notions of their own productivity?

Unfortunately, yes.

When Faster Means Slower

We're generally quite bad at assessing our own productivity accurately. Whether we've really become more productive through something isn't always easy to answer, and often we're just completely wrong.

This is partly because "feeling productive" and "actually being productive" aren't exactly the same thing. For example, we remember successful projects much better than failures.

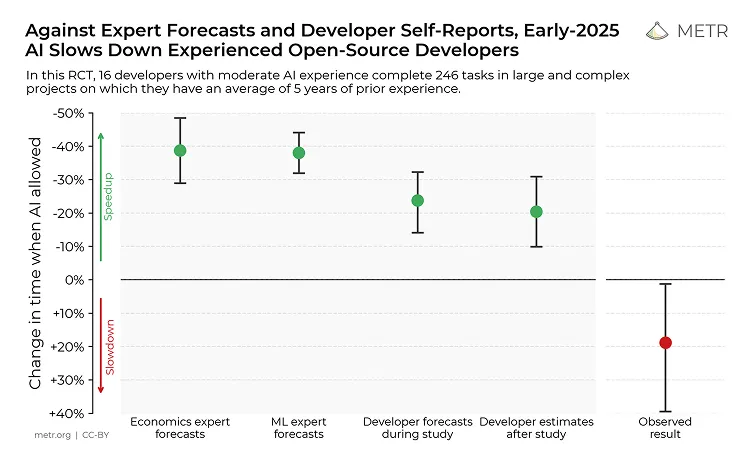

Using actual software projects as an example, a recent study shows exactly this phenomenon: One group of experienced software developers used AI for their ongoing projects, a second group did not.

Before the project work, the AI group estimated they would be 25% more productive through AI. After completing the project work, they were surveyed again and actually felt they had been about 20% faster with AI than without.

The actual result: The group with AI was 20% slower than the comparison group.

In other words: Software developers who use AI often feel significantly more productive in their work – but in reality may be significantly less productive. Not very reassuring: While the developers' estimates were completely off, they were still significantly better than those of economists and AI experts surveyed in the same study.

What applies to software development also applies to other activities. There are moments when we accomplish a whole day's work in two hours – and we remember those vividly. We repress the moments when we desperately try to get an AI to work out something we could have done ourselves in a short time.

The Flow of Illusion

It can feel very productive to develop a text idea or structure a presentation in a vivid back and forth with an AI. The lively flow of interaction feels like progress. A phenomenon that AI coding platforms like Lovable consciously exploit, by the way: They generate an addictive feeling of progress in before users realize that in reality everything is much more complicated than they thought (coincidentally, right after the paywall kicks in).

Meanwhile, it can seem like stagnation to sit and think in silence, only pen and paper in hand. Or one fears the accusation of laziness when going for a walk to develop clear thoughts.

Even if these strategies result in a same – or a better – result after the same amount of time, only one of them maintains the outward form of productivity. In many organizational cultures, "I am sitting in front of a screen and typing things" is the true manifestation of work – everything else requires explanation.

Conclusion: Using AI Without the Rose-Tinted Glasses

All this doesn't mean, of course, that generative AI is useless!

Because while the feeling of being productive deceives us more often than we think, there objectively are situations where we save many hours of work through AI: Creating interchangeable boilerplate code, explaining technical documents in layman's terms, writing summaries, and many other tasks can be done excellently with generative AI. The English version of this text, for example, was created by Claude, with half an hour editing by myself.

However, we don't identify these limited, clearly defined cases with one prompting framework or whitepaper, but by reflectively exploring the technology and thereby intuitively understanding what it can and cannot do. This means a lot of experimentation, exchange, and also training formats that don't advertise productivity miracles but offer realistic assessments.

Less Hype, More Confidence

Dealing with Artificial Intelligence, we would probably benefit from more self-confidence.

More self-confidence in the face of AI experts on LinkedIn and YouTube, whose whitepapers, frameworks, and prompt libraries rarely deliver what they promise.

More self-confidence in the face of promises and predictions of CEOs who primarily want to sell their own products.

And above all, more self-confidence in evaluating our own experiences: If despite all attempts you still haven't become a 10x employee with AI and on the hundredth try still get made-up answers to simple questions, it's not your fault.

It's probably simply due to the limitations of a technology that, while still falling short of many expectations, can nevertheless be an excellent tool – especially when we approach it not with blind enthusiasm, but with healthy skepticism and a lot of curiosity.