Efficiency is king—if you're still working hard, you've already lost. So we let AI do the heavy lifting: fast, convenient, but prone to error. But what happens when we outsource our thinking too often? Kolja Wohlleben explores this question—and reveals why efficiency may help us move forward, but can also make us mentally lazy.

Good bosses don’t reward hard work.

In well-run organizations, it’s outcomes that count—not how much effort we expended to get there. The question isn’t: “Who worked the hardest?” but rather: “Who delivered the best result as quickly as possible?”

The path to success is the one of least resistance

We set performance goals, not effort goals. Calling someone “results-oriented” is praise, “They always tried their best” is a scathing review. And it should be!

Ideally, this pushes us to act efficiently, intelligently, and with focus, rather than working extremely hard on the wrong things.

At the same time, we’re naturally wired to avoid exertion: wasting energy isn’t exactly an evolutionary success strategy. That’s why we have computers do the math, use heuristics, and treat simple explanations as more likely to be true.

As a consequence, achieving good results with minimal effort is usually the optimal strategy—but one that comes at the cost of cognitive fitness.

When we avoid mental strain, we trade skill in specific tasks for overall job efficiency. The accountant who insists on doing yearly reports with pen and paper might be amazing at mental arithmetic—but also unemployed quickly.

Reading and Writing: The Original Digital Dementia

Every time new technologies ease our workload, the same old fear returns: Are we now getting dumber?

Back in 2010, for instance, The New York Times wondered if cell phones were harming our long-term memory since we no longer memorize phone numbers. (The author's questionable response: Probably not—because now we have to remember more passwords instead!)

The classic case, of course, is Socrates defending his illiteracy by arguing that writing damages memory: “This invention will implant forgetfulness in the souls of learners by causing them to neglect their memory.”

So far, the answer to whether new technologies make us dumber - or otherwise degrade our mental capabilities—has generally been: not really.

Technology Enables Complexity

Some skills become less necessary, and we shift our focus to other, often more complex, things. In math class, we eventually allow students to use calculators so they can tackle algebra or calculus. It’s actually more plausible that, until recently, humans have been growing smarter—driven by technological progress and increasingly complex environments.

But we’re now hearing it again: technology—this time, AI—is making us stupid.

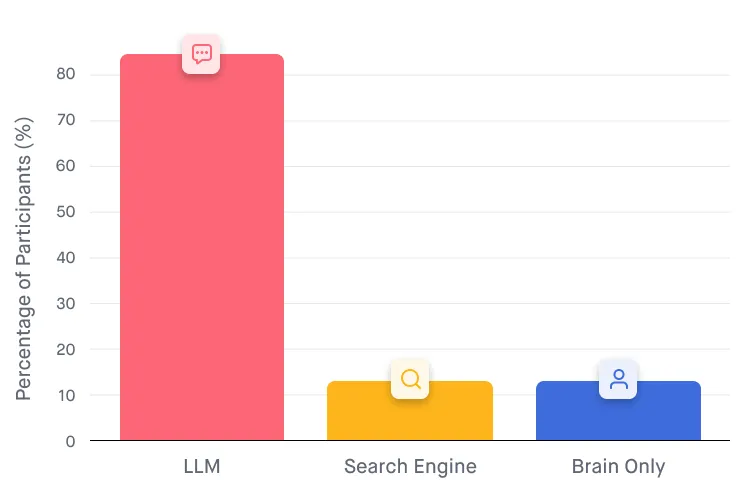

A viral MIT study supposedly shows that using LLMs causes “cognitive atrophy.”

Your Brain on ChatGPT

In the study (Your Brain on ChatGPT), participants were asked to write essays on topics like “Is a perfect society possible?” One group was allowed to use ChatGPT. Unsurprisingly, they outsourced much of the thinking. Their brains were significantly less active—and just a few hours later, many couldn’t recall a single line from their “own” texts.

Effort is essential for building new neural connections. So it’s not exactly shocking that the group who had full essays generated for them retained the least from the experience.

But in reality, we rarely require employees to write essays about the possibility of perfect societies. So what does this study really tell us—other than the obvious fact that when you write less, you remember less of it?

First, the good news: the study doesn’t show that “ChatGPT makes you dumber,” despite what some articles—whose predictability itself could pass as an AI output—have suggested.

To quote the study’s authors (in words that, ironically, many didn’t read):

“No! Please do not use the words like ‘stupid’, ‘dumb’, ‘brain rot’, ‘harm’, ‘damage’, ‘passivity’, ‘trimming’ and so on. It does a huge disservice to this work, as we did not use this vocabulary in the paper, especially if you are a journalist reporting on it.”

What the study does show is that we use our brains less when we don’t have to use them—exactly what you’d expect from efficiency-driven effort-avoiders.

Hand over Work, Give up Understanding

The less encouraging part is that this doesn’t just apply to essays and homework. For tasks like market analysis, contract review, or data evaluation, the temptation and incentives to take shortcuts may be even greater.

And often, those shortcuts work: whether it's a market analysis, contract check, or data report—they all can be done quickly and, at least superficially, well.

One problem is that this sometimes results in convincing documents based on completely fabricated information.

But more importantly: market analyses, contract reviews, and data evaluations aren’t just the documents we produce. They’re also the processes that help us act more intelligently in the future.

Put simply: delegating these tasks to AI might give us a market analysis—but not an understanding of the market.

It’s not clear that, going forward, we’ll always be given enough time and incentives to build that understanding. Sure, deeper insight is always valuable—but it’s a value that comes at the cost of slow, human effort.

The famous cliché about AI’s impact goes: “You won’t lose your job to AI - you’ll lose it to someone who uses AI better than you.” But from a business perspective, “better” often doesn’t mean someone who built deep understanding during the process—it means someone who delivered an acceptable result, fast.

So the employee who passes along an AI-generated report, barely reviewed, to an uncritical boss, may have, in fact, made the “better” call.

Knowledge is the Residue of Thought

So - does AI really make us dumb? That claim is too simple. But it’s at least more plausible than it was with calculators or writing. Because the incentive structures of our organizations, combined with our own laziness, might indeed be slowly undermining our grasp of complexity.

But: understanding complexity, critical thinking, and experiential knowledge are also competitive advantages. And we only develop those if we use new technologies wisely—avoiding the very “cognitive atrophy” we’re warned about.

Knowledge is the residue of thought. And only if we keep thinking for ourselves will there be knowledge left at all.